What the experts say

In Germany, “several technologies to increase efficiency have so far been rarely used, although they are available on the market and provide relatively cost-effective mitigation options.” – Federal Environment Agency (UBA)

“(We) believe that the (emissions) reduction levels proposed by the (European) Commission for 2025 and 2030 are too aggressive (…) The ambition level for 2025 is too stringent given the short deadline for this first-ever CO2 target.” – Association of European Automobile Manufacturers (ACEA)

“Trucks have been responsible for nearly 40% of the growth in global oil demand since 2000; It is the fastest growing source of demand for oil, especially diesel. Without further policy efforts, trucks will account for 40% of oil demand growth, and 15% of the increase in carbon dioxide emissions in the global energy sector, until 2050. – IEA

the problem

More than 95% of carbon dioxide emissions in Germany’s transport sector are caused by road traffic, and about a third of this is caused by long- and short-distance road transport, according to the state-funded German Traffic Research Portal. While the country’s total emissions have fallen by about a third since 1990, carbon volumes have remained largely stagnant in the transport sector over this period, and have even increased slightly in recent years due to the decline in biofuel use and the sustained boom of the German economy. Although nationwide road tolls were introduced for freight trucks in 2005, traffic volume growth has outpaced economic growth since then.

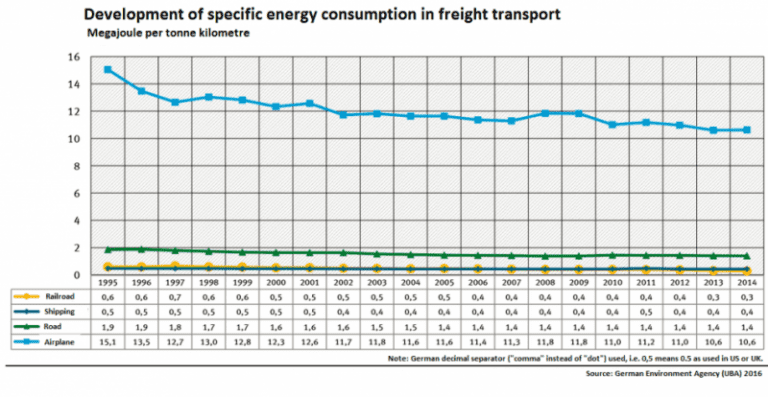

Temporary reductions in CO2 levels were made possible by increased engine efficiency, but also resulted from replacing petrol with diesel and frequent refueling stops at service stations close to borders abroad, where fuel is often cheaper than in Germany, he says. FIS.

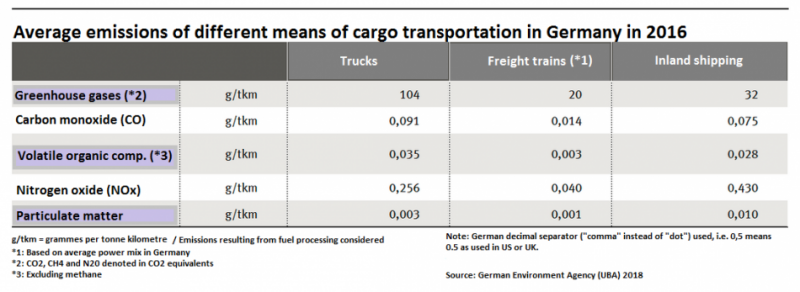

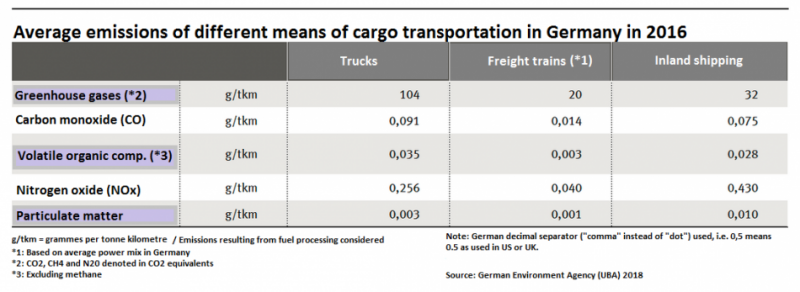

However, while the specific emissions from road transport are greater than those from long-distance inland freight or rail transport, the difficulties of creating suitable infrastructure for the latter two vehicles make trucks and other freight vehicles the most energy efficient way to transport goods. Bulk. Over shorter distribution distances, according to the Heidelberg Institute for Energy and Environmental Studies (IFEU).

Trucking dominates the country’s freight logistics industry, transporting 73 percent of all goods traded domestically and internationally, followed by rail transport at about 18 percent, and domestic freight at just over 9 percent.

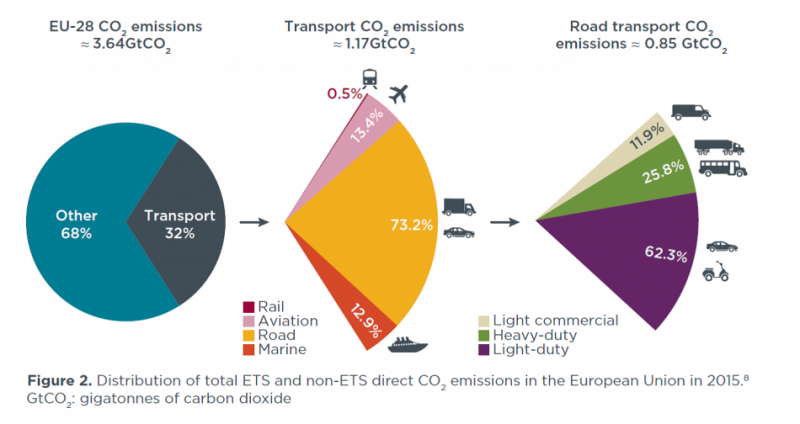

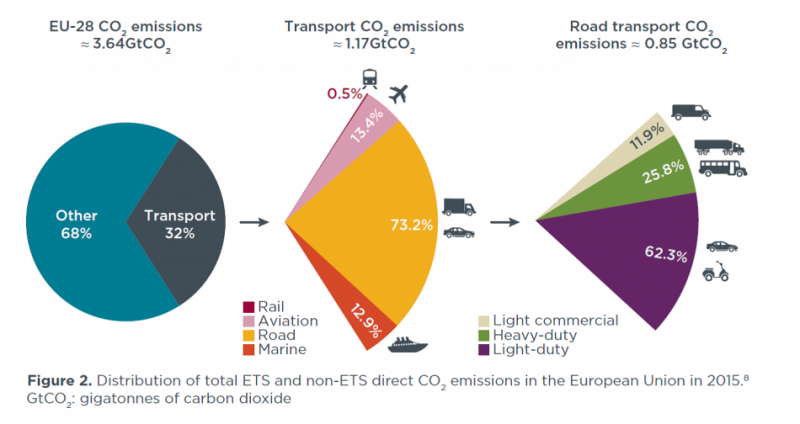

Across Europe, freight vehicles were responsible for about a third of CO2 emissions from road transport in 2016. This figure could soon reach 40%, as passenger car emissions are expected to gradually decline – while emissions from road transport do not. Trucking.

The Federal Office for Goods Transport (BAG) says more than 40 percent of trucks on German roads and motorways are registered abroad. Most of these companies are shipping companies from Eastern Europe, which often cater to German customers.

Despite the large number of international shipping companies active in Germany, the country’s domestic fleets of trucks, light-duty trucks, tanker trucks and semi-trailers lead Europe in terms of volume, carrying 310,142 million tonne-kilometres annually. Most of them are within the country. In recent years, shipping volume, emissions and profits have risen, reaching a temporary high in 2016.

Currently, trucks are not subject to CO2 emissions or fuel consumption standards either in Germany or at EU level. For this reason, unlike automobiles, trucking has not seen significant advances in e-mobility and fuel efficiency.

According to a report in the energy policy newsletter Tagesspiegel, German EU Commissioner Guenther Oettinger recently sought to water down a joint initiative by several member states to tighten European emissions limits for trucks – the first of its kind.

Under the scheme, the carbon emissions levels of new trucks – first the largest and then the smallest – must be 15% lower by 2025 based on 2019 levels, then another 15% by 2030. The same legislation would stimulate the use of new trucks. Heavy duty freight vehicles with low and zero emissions. According to EU experts, this could reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 54 million tons (equivalent to Sweden’s annual emissions) between 2020 and 2030. Moreover, it would save trucking companies a lot of fuel.

Naturally, in the wake of the “dieselgate” scandal, measuring compliance with emissions regulations has become crucial. Authorities must monitor “real-world fuel consumption data” based on mandatory, standardized fuel consumption meters, and impose penalties for non-compliance – a necessity that remains difficult to implement for passenger cars.

While the EU targets may be considered too ambitious by carmakers, a coalition of 36 freight forwarders, associations and transport companies – including DB Schenker, Siemens, Tchibo and five countries (Germany is not among them) – has lobbied for Reducing emissions by 24%. Reduction by 2025. They insisted that the transport sector would not achieve the goals set in the Paris Agreement, otherwise.

The dilemma

There are a whole range of suitable options for reducing carbon emissions in road freight transport, from the introduction of hybrid trolleybuses or limits on exhaust pollutants to green freight programs and fuel efficiency labeling. Studies show that trucks and semis can achieve significant gains in fuel efficiency through improved engine technology and aerodynamics, which could reduce the carbon footprint of, for example, tractor trailers by 40 percent. Electrification of freight logistics could help reduce road freight emissions by more than a quarter by 2050.

German luxury automaker Daimler, which is also the country’s largest truck producer, recently showcased a range of options it has researched to make its vehicle engines more sustainable and meet the EU’s 2030 vehicle emissions limits. The company says hybrid engines are not a solution for heavy vehicles because they cannot Use them in an economically viable way, arguing that conventional diesel engines still have untapped potential to reduce emissions by 10 to 20 percent.

According to Daimler researchers, diesel trucks remain far superior to electric trucks when it comes to energy efficiency. They argue that a truck filled with 224 liters of diesel fuel will have the same range as an e-truck with an eight-tonne battery. A potential remedy to the difficulty of installing economically viable batteries in heavy vehicles could be Germany’s first e-autobahn, a concept currently being tested in the federal state of Hesse and funded under the country’s 2020 Climate Action Programme. The trucks use a catenary system (overhead electrical wires) to charge their batteries as they travel along the five-kilometre highway. The pilot course was designed and run by industry heavyweight Siemens, Technical University Darmstadt, and five transport companies – and could be replicated across the country if successful.

There are also strategies and pilot projects aimed at encouraging the switch to alternative fuels (hydrogen, liquefied natural gas, synthetic fuels, renewable methane), redesigning the road toll system in favor of zero-carbon or low-carbon trucks, or increasing the diesel tax. In June 2018, the German government established a support program for freight vehicles powered by more efficient, low-carbon engines. Shipping companies receive grant payments of up to 40 percent of the additional cost of modern freight vehicles or lump sums for specific technologies, for example €40,000 for e-trucks weighing more than 12 tons.

According to Germany’s Federal Environment Agency, reform of the toll system for heavy goods vehicles is necessary to reveal the “true cost” of road transport. Possible reforms include expanding the range of vehicles weighing less than 7.5 tons; including emission levels in the tariff system; Or amazing road pricing based on efficiency standards. If trucks and trailers were forced to pay punitive duties and carbon costs under the “polluter pays” principle, their competitive advantages over rail would diminish, UBA says.

For the “last mile” of goods transport in inner cities, the expanded use of cargo bikes and pedal cycles (electric pedal cycles) is a clear possibility that is already being tested on a large scale. Projects such as logSPAZE implemented by Fraunhofer IAO in Stuttgart are testing alternative urban delivery concepts using pedal-powered vehicles in cooperation with local companies to find out the most suitable solutions to mitigate traffic levels and reduce emissions and air pollution in densely populated areas.