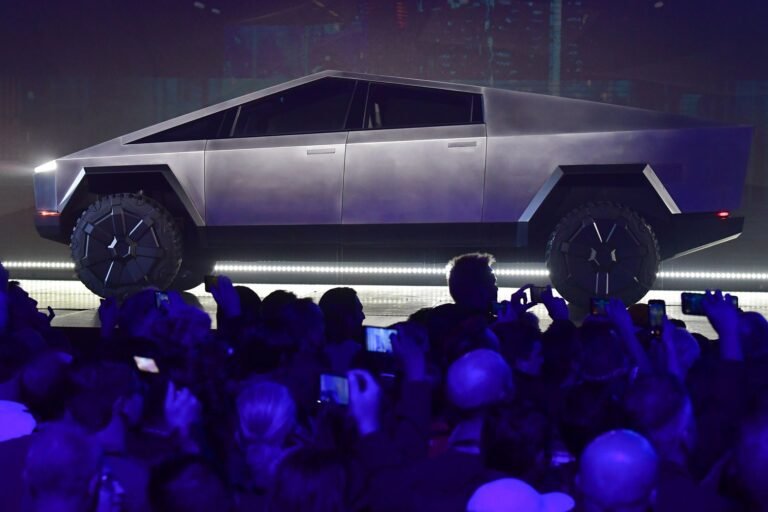

With its sharp angles, trapezoidal body, and stainless steel (and supposedly bulletproof) exterior, the Tesla Cybertruck looks more menacing than any regular car. So it was no surprise that urban planning and road safety advocates reacted to the recent Cybertruck delivery event with dismay and anger. The Center for Auto Safety posted that it “poses a danger to anyone else on the road”; Urban collective Streetsblog posted a story titled “How to Build a Car That Kills People: Cybertruck Edition.”

I have some bad news for those who fear the Cybertruck’s impact on road safety: No matter how dangerous the vehicle is, federal officials are powerless to prevent its sale or use on public roads. Even if the Cybertruck turns out to be as deadly as some observers expect, federal officials’ hands will be tied for a long time. Whether we like it or not, this regulatory deficit has become part of America’s laissez-faire approach to car safety.

Right now, little is known about how dangerous the Cybertruck really is. The federal government has not shared safety ratings, nor has the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, which conducts its own crash tests. However, much of what we can ascertain from press releases, photos and videos appears to be worrying. And the Cybertruck’s most troubling features aren’t necessarily the ones that have drawn the most criticism.

Raul Arbelaez oversees the IIHS Vehicle Research Center outside Charlottesville, Virginia, where he spends his days monitoring what happens when cars hit things. He told me he’s evaluated the safety of hundreds of car models, though he’s yet to get his hands on a Cybertruck. But based on what he saw in a video of the Cybertruck hitting the wall, he’s ignoring the social media panic over the Cybertruck’s alleged lack of a crumple zone (a design feature that allows a crashing vehicle to collapse like an accordion, absorbing much of its force). From Arbelaez’s perspective, nothing in this video seemed out of the ordinary. “And even if I were observing it personally, I would never be able to make a judgment without downloading the logs from the dummy and accessing high-resolution data about how the bodywork intrudes around the occupant,” Lee said.

But other aspects of the Cybertruck’s design raise red flags for Arbelaez. In particular, he is concerned about the car’s many sharp edges, which seem capable of cutting a person who is pushed against them. “Anytime a body part hits a hard edge, that’s a concentration of stress,” he said. “You will cause additional damage.” He’s also concerned about what the Cybertruck’s stainless steel exterior could do to a human. “If one of your body parts, especially the head, hits a bulletproof plate as well, that plate may not give much,” he said. “Would you rather fall on a concrete sidewalk or a pile of pillows?”

The Cybertruck’s unique high front end can increase the risk of head-on collisions, especially when hitting those walking, biking or in a wheelchair. Last month, the IIHS released new research finding that vehicles with a higher, more vertical front end are significantly more likely to kill pedestrians.

Other aspects of the Cybertruck’s design are almost certainly serious, but they’re not unique. At about 6,800 pounds, the Cybertruck weighs more than two Honda Accords. This is found in the top end of the car models, but others are heavier. (You’d need to add a third Accord to reach the Hummer EV’s weight.) All other things being equal, heavier cars transfer more force in a collision, covering a greater distance before coming to a stop when the driver hits the brakes with force.

The Cybertruck’s excessive power is another concern, and an important one. Tesla claimed last month that the high-end “Cyberbeast” version would go from 0 to 60 mph in 2.6 seconds. This pickup is comparable to a Formula 1 race car, and far exceeds the unnecessary acceleration that competitors already offer, such as the Ford F-150 Lightning that can go from 0 to 60 in less than 4 seconds. Although this power poses obvious risks to other street users who lack the time to get out of the way, its practical value is questionable. “The Cybertruck is a 6,000-plus-pound piece of steel that can’t do a quarter-mile in less than 11 seconds,” Jennifer Homendy, head of the National Transportation Safety Board, told me. “Why do we need that?”

To sum it up, we don’t yet know how dangerous the Cybertruck really is, but some of its design choices are worrying, especially when taking into account the car’s massive weight and powerful engine. Given Tesla’s myopic concern for the occupants of its cars (“If you get into an argument with another car, you’ll win,” Musk promised), the potential danger to other street users is real.

Now we get to the crazy part: Even if panicked federal auto regulators wanted to pause or slow down the Cybertruck’s rollout, they probably couldn’t. “I don’t know of anything that NHTSA could do within its legal framework to prevent something like the Cybertruck (launch),” Arbelaez told me.

The reason has to do with self-certification, a fundamental principle in US vehicle regulations. Self-certification works pretty much as it sounds: Automakers are free to design and sell whatever they like, as long as they certify (with a sticker) that each vehicle adheres to the encyclopedic Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards. The FMVSS sets design standards for specific items such as seat belts and steering wheels, but contains massive omissions (i.e. no reference to pedestrian safety or maximum acceleration). Updating it takes years.

As long as automakers like Tesla don’t explicitly violate the FMVSS, they’re free to use whatever designs and features they want in the United States. Although Elon Musk said in a recent podcast that the Cybertruck has “passed all regulatory tests,” no such tests are needed — or even available — from the federal government before launching a new vehicle. Tesla just needs to give itself the green light.

If an FMVSS-compliant vehicle appears dangerous, NHTSA can only intervene after launching an investigation that identifies a pattern of related incidents (often crashes). “NHTSA has subpoena authority, but they have to wait for something to happen before they can take action,” the NTSB’s Homendy said. Meanwhile, faulty vehicles are driving on the road, putting everyone in danger.

It’s a whole other story across the Atlantic, as Musk himself seems to understand. Speaking last year in Berlin, he joked: “In the US it’s legal by default, in Europe it’s illegal by default.” He’s not wrong.

In the European Union, an automaker seeking to sell a new model or feature must first obtain a government green light known as type approval. This can be a cumbersome process, as regulatory staff conduct tests and sift through data. EU regulatory bodies have real power; They’ve already forced Tesla to tweak its Autopilot system to provide certain safety features to all car owners, not just those who access them through gaming.

Although Tesla has promised to make the Cybertruck available to US consumers next year, the company has not shared any time frame for doing so in Europe. Given Europe’s stricter regulatory regime, this should not be surprising. IIHS’s Arbelaez noted that the Cybertruck may be particularly vulnerable in the European Union because its regulations, unlike U.S. regulations, evaluate the effects of pedestrian collisions.

Have European car safety regulations prevented rash car designs and reduced crash deaths? Answering this question is extremely challenging, because it requires separating the influence of vehicle design from a myriad of road safety variables (speed limits, car ownership rates, and drunk driving rate, to name a few). What we do know is that Europeans are much less likely to die in crashes than Americans, whether deaths are measured by population or miles driven. It is difficult to see how the rapid deployment of new models like Cybertruck could help the United States close this gap.

Predictably, automakers hate the idea of the federal government adopting a European-style pre-approval system for cars, which would require significant investments of time and money. But this concept has precedent. For decades, the United States has used a type approval framework for aviation oversight, requiring the FAA to inspect new aircraft designs and technologies before they are deployed.

David Zipper

Important people are noticing how bad the CLEAR condition of airports is

Read more

The FTX Saga Twist That May Save SBF in Judgment What’s Happening with Kara Swisher’s Book Tour? Sandworms in the dunes may not be worms, exactly how can you avoid getting killed by a sandpit on the beach. Yes, parents need to know this.

This system seems to work well. Earlier this year, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg noted that American aviation is the safest in the world, with only two people dying in commercial plane crashes in the United States from 2010 to 2021. But the American track record in road safety No less terrible than flying. Performance is excellent. On a per-passenger-mile basis, driving in the United States is more than 100 times more dangerous than flying, and no other wealthy country in the world has residents at a similar risk of dying in a car accident. Residents of Canada, its vast, car-centric neighbor to the north, are only 40 percent likely to be killed in a car crash.

Even at this early stage, it is certain that Tesla’s design choices for the Cybertruck will not reduce American accident deaths, but may even increase them. If the car proves to be as deadly as some fear, it will take time — likely years — before federal officials can intervene to protect everyone not inside.

For everyone’s safety, perhaps Musk should ask for permission, rather than forgiveness, before unleashing his next horrific ideas on America. Streets.

Future Tense is a partnership between Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that studies emerging technologies, public policy, and society.